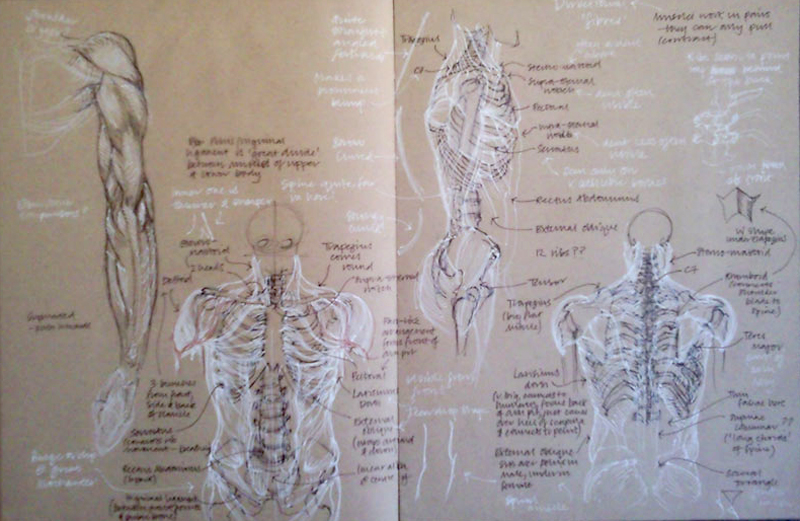

Simplifying the skeleton

The skeleton can be an intimidating thing to approach, not for it’s halloween persona or supernatural qualities but simply because of its complexity. Not just in form with its processes and tuberosities but also in language with its profusion of latin names and terms. Once I started to become familiar with some of the terms and their meanings, things started to make much more sense; mastoid process for instance can be translated as ‘teat-like lump’. Knowing things like this stops the skeleton feeling like a foreign country.

Etymology Anatomica

The anatomy almanac is an entertaining illustrated guide to the origin of various anatomical terms.

For a more direct reference try the straightforward but useful alphabetical glossary of latin anatomical terms.

Function and the primary forms:

The idea of simple description also holds the key to conceptualising the skeleton for artists.

I think of the skeleton as the primary structure of the body; it offers support, transferring the body’s weight to the ground, protection, of the important bits, and it allows movement.

The primary forms can be described as:

- Skull – a very rough sphere at the back, with longer, flatter top, sides and front. The skull contains and protects your brain.

- Spine – an angled tube with a suprisingly strong ‘s’ curve. The spine is the body’s main column and conduit.

- Rib-cage – an egg with a flattened angle top. Contains and protects the heart and lungs.

- Pelvis – an open fronted bucket or butterfly figure of eight. Holds up the intestines and articulates the legs with the spine.

- Arm and shoulder – open ball joint at the top of the arm with a combination of hinge and swivel at the elbow, articulated to the rib-cage by a bent coat hanger.

- Leg and foot – closed ball and socket joint at the top of the leg, open hinge at the knee with interlocked pivot to the wedge of the foot.

Locate and relate

When drawing a skeleton I usually use a standard proportion, making the skeleton 7 1/2 heads high. I put the 1/2 head in the middle because it gives much more convenient measures for the knees and it encourages me to check the actually halfway point when I do work from the figure. It is normally somewhere around the pelvis but varies significantly different individuals.

I use a centre line to align the ear, shoulder, hip knee and ankle, with the masses roughly balancing either side. Using a straight centre-line also highlights the curve of the spine and its relationship to the other curves of the body, both outer form and inner movement. The angular alignments of the masses can also be helpful in describing the tilts and orientation of the key masses.

How it helps

Thinking about the forms of the skeleton in this way helps to generate a volumetric concept of the body and hence to create a drawing which represents that volume.