Drawing has an interesting relationship to memory. When you draw from your imagination you are in essence drawing from memory, your imagination being comprised of reconstituted fragments of your personal visual library, albeit reconstituted according to your own ideas and direction.

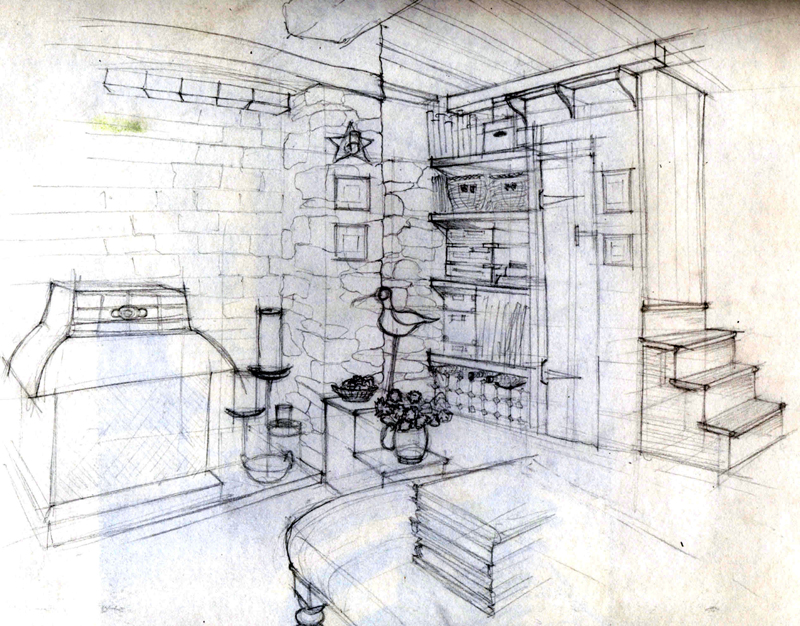

Sketchbook memories

I have remarked before in my Sketchbook that I have incredibly clear memories of sketches I have made in the past. My memories extend far beyond what the subject looked like; I can recall how I sat or stood and on what surface, if I was hungry, or rushed, the pen I used, how tired I was, who I was with, the weather, temperature and my feelings about the subject, excitement, wonder or curiousity. It makes a strong case to leave the holiday camera at home, afterall, how many photos do you have that you can barely remember taking, even when they are in front of you?

Memory drawing

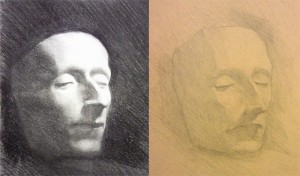

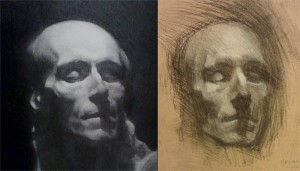

I’ve tried a couple of specific memory drawings of my casts and life drawings. I found that I have to begin at the same point as I began my original drawing and proceed almost line by line as I had before. It’s astonishing, I can usually recall a reasonable image, although it does not support close scrutiny, yet I can reconstruct not only my original impressions as I drew but my responses too. It’s an example of the body’s own haptic memory. It is incredibly powerful. I have heard from one of my tutors that art students of the past, very well trained in the specific techniques of memory drawing, used to go to the galleries, utilise those techniques they had learned and return to their studios. There they produced excellent copies from the master works they had visited in the galleries.

You are a memory magician

These same abilities are used by memory magicians, although I think the techniques are a little different. In his book on the subject Derren Brown explains one technique for memorising a list of items by locating them, in your imagination around a familiar room in your house, using your usual movement around that space to ensure the correct order of items. I’m sure we use these abilities regularly in our daily lives, for instance, have you ever driven on a long journey in which you don’t remember long sections of the trip? Yet you arrived safely, your body may have remembered that right turn, or the correct exit on the roundabout.

Ideated sensation

If I say to you, ‘Ring a ring o’ roses, pocket full o’ posies…,’ or ‘Heads, shoulders, knees and toes, knees and toes…,’ (please select a couple of language/culture specific nursery rhymes here if required) you’re likely to remember the rhyme, its rhythmn, maybe the words, probably some visual impressions related to singing those rhymes and almost certainly the actions associated with them and the touch of other hands in a circle. That is the ideated sensation, a multi sensory ‘mind’s eye’, and it is as relevant to current imaginings as it is to past experiences.

Discussing memory drawing my tutor noted that any errors made in the original drawing were always exaggerated in the memory drawing.

This is a good tool for finding subtle drawing errors but it goes further that that, to the ideas which to create that impression:

“a truth of impression as well as of form, of thought as well as matter, and the truth of impression and thought is a thousand times the more important of the two.”

Ruskin

School of memory

One sports study (at the University of Chicago) examined visualisation (actually a misnomer for a fuller sensory experience) in basketball training. They studied two groups, one engaged in an extra physical practice, the other in an extra visualisation practice, both groups also continued their usual baseline training. The study found that the group engaged in visualisation performed better after the extra training, reasoning that the visualisation had reinforced only the postive ideas, whereas training also reinforced errors in performance. That is, the idea was stronger than the reality.

Some artists of the past advocated setting up schools on this principle, one was Robert Henri,

“the model might hold the pose in one room and the work might be done in another. The pupils would have their places in both rooms, one for observation and the other for work….into this room he carries only what he knows.”

Since we really see with our minds not our eyes, this I think would produce a purer version of the ideas that go to make up our impression and concentrate the efforts of pupils on building their ideas. Greater awareness is needed to really develop such a skill.